Sat 09/19/15 7:30pm-

Tue 09/22/15 7:30pm-

Fri 09/25/15 7:30pm-

Sun 09/27/15 2:00pm-

Luisa Miller–

William Berger–

Verdi’s career was so remarkable that it works against a proper appreciation of his genius—there’s almost too much great Verdi work to comprehend. Anyone can weary of the superlatives: the “tragic grandeur” of Otello and Rigoletto, for example, or the “awesome vastness” of Don Carlo, or the “brilliantly penetrating psychology” of La Traviata. Yet the superlatives are justified and necessary. Throughout his career—and especially from around the time of Luisa Miller (1849) onward—Verdi composed a canon of masterpieces, each with its own tone or tinta as he called it, that amaze us by their diversity from each other as well as by their individual merits. And for clear, unaffected, gem-quality exploration of genuine human emotion, no opera exceeds Luisa Miller.

The source material was good: the play Kabale und Liebe, (Intrigue and Love), by the great German author Friedrich Schiller (1759–1805), once popular among composers (Verdi’s Don Carlo, Giovanna d’Arco, I masnadieri, and parts of La Forza del Destino are inspired by his works, as are Donizetti’s Maria Stuarda, Rossini’s Guillaume Tell, and the chorus of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9, among others). The outline of the play is fairly straightforward: The son of an official at a ducal court in the Tyrolian Alps and the daughter of a middle-class musician fall in love; the boy’s father wants him to marry the duke’s mistress instead; plots are concocted to ruin the love affair, and the girl’s parents are arrested; in order to save them, she writes a false letter expressing love for another man and swears it is true; the boy confronts her and, as she dies, she reveals the truth. The crux of the drama is the confrontation of middle and upper class worlds. Representing the middle class on stage at all was an aspect of a radical new genre, the “bourgeois tragedy.” Before this time, tragedy was the exclusive domain of the nobility. This was more than mere elitism. Nobility and royalty by definition represent multitudes of people: hence Shakespeare’s confusing use of titles for characters, (cf. “Norway” in Hamlet). We see the same phenomenon in many languages (but not English) today: the vous/voi/vosotrosforms in the Latin languages, ihr in German, etc. Important people were plural personages, and the outsized emotions of classic tragedy are right-sized. In the eighteenth century, German writers began ascribing the same grandeur to common individuals, and the result, while fascinating, seemed extreme. This is partly why people spoke of Sturm und Drang (storm and stress) to describe these dramas. The emotions had not grown; the people expressing them had “shrunk,” in a sense. Making this same transition from nobles to commoners was a similarly fraught process, and the operas of the later nineteenth century dealing with everyday people are the ones people think of as shrill. It was fine for royals in early operas to wail and gesticulate extravangantly, but when “common individuals” like Santuzza in Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana express the same levels of emotion, suddenly opera becomes overwrought for many people. Verdi negotiated the conflicting parameters brilliantly, especially in Luisa Miller.

In 1849, the opera was contracted for the great San Carlo opera house at Naples, whose reactionary air was uncongenial for the radical Verdi. In fact, he swore he would never produce another opera there (and he never did, despite a tortured attempt with Un Ballo in Maschera in 1859). But he did get to work again with the great Neapolitan librettist Salvadore Cammarano, with whom he had just collaborated on the sensationally patriotic opera La Battaglia di Legnano in Rome. More famously, Cammarano had written the excellent libretto for Donizetti’s Lucia di Lamermoor in 1835. (Verdi would collaborate with him once again on the intense Il Trovatore in four years, and Cammarano died before completing that libretto). Cammarano streamlined Schiller’s drama marvelously. There were few last minute changes, and no subsequent edits. What the seasoned professional Cammarano wrote is what we get today.

Naturally, the journey from drama to opera was not painless—it never is. But the necessary streamlining served to shift the focus of the story. Schiller’s critique of court life and the tyranny of petty German despots—the Kabale (Intrigue) of the title—is curtailed whileLiebe (Love) is emphasized. This is not a case of Verdi pleasing the royalist censors of Naples (although he did accomplish that). The fact is that Verdi had found a deeper way to be political when he wrote Luisa Miller than he had formerly expressed as the chief musical mouthpiece of Italian patriotism.

From Nabucco (1843) on, Verdi had portrayed themes of national uprisings against unjust tyrannies, providing inspiration and (in many cases) actual rallying choruses for the emerging Italian unification movement, the Risorgimento. The point was to inspire members of the audience to walk out of the theater and immediately take up arms against the (mostly Austrian) enemy. By late 1849, the situation had changed. The wave of revolution that erupted in 1848 was fizzling out. By the time the year was over, the forces of reaction had clearly reestablished themselves more grimly than ever. The desired change would not happen on the barricades of Paris, Milan, Dresden, or anywhere else. The revolution would have to be something other than what had been imagined. Richard Wagner, exiled from Germany after his involvement on the front lines of the rebellion, would recalibrate his revolutionary hopes and find renewal in national mythology. Verdi would find it in individuals.

It is a mistake to think that “the political Verdi” refers only to the patriotic choruses of his early operas. Verdi’s true and radical political idea was expressed in the notion that the needs of the individual, no matter how humble, are as important as the needs of the great and mighty. Put another way, if we remember the concept of nobles as metaphors for groups of people: the needs of the one can outweigh the needs of the many. So it is in Verdi’s Aida (1870), when the slave girl—the socially lowest person on a stage teeming with kings, priests, and generals—shifts the focus of the entire massive vocal ensemble in the Triumphal Scene to herself with a solo vocal line. And so it is when the prostitute Violetta in La Traviata demonstrates that she alone is the moral compass of her social milieu. There are other cases of Verdi drawing riveting portraits of the individual against society and its dogmas (Stiffelio, Boccanegra, et al.). In Luisa Miller, this preference for the individual is present in both the story itself and in the choice of available material from Schiller.

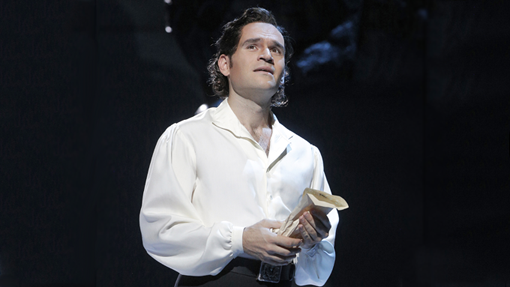

It is a mistake to think that “the political Verdi” refers only to the patriotic choruses of his early operas. Verdi’s true and radical political idea was expressed in the notion that the needs of the individual, no matter how humble, are as important as the needs of the great and mighty. Put another way, if we remember the concept of nobles as metaphors for groups of people: the needs of the one can outweigh the needs of the many. So it is in Verdi’s Aida (1870), when the slave girl—the socially lowest person on a stage teeming with kings, priests, and generals—shifts the focus of the entire massive vocal ensemble in the Triumphal Scene to herself with a solo vocal line. And so it is when the prostitute Violetta in La Traviata demonstrates that she alone is the moral compass of her social milieu. There are other cases of Verdi drawing riveting portraits of the individual against society and its dogmas (Stiffelio, Boccanegra, et al.). In Luisa Miller, this preference for the individual is present in both the story itself and in the choice of available material from Schiller.As always in Verdi, we learn about a character’s true humanity through his or her singing. Melody would become suspect by the end of the nineteenth century and almost regarded as an enemy in the twentieth. In many operas of the early nineteenth century, however, it expresses levels of sincerity. In Donizetti’s Lucia di Lamermoor, the tenor Edgardo is not sympathetic in the synopsis. His quickness to believe the worst (a character defect common to operatic tenors) makes us question the sincerity of his love for Lucia. Yet no one who hears his melodies—especially his final Tomb Scene—can doubt his love. Melody validates him. This sounds tautological but it was not done the same way before Donizetti (perhaps with Cammarano’s influence). Mozart does not use melody in this dramatic way: you can’t tell who is sincere and who is not by the beauty of the melodies in Così fan tutte, just to cite the most glaring example. But Verdi learned Donizetti’s lesson well. In Luisa Miller, the tenor role, Rodolfo, doesn’t transcend the hoariest clichés about the species when we read the synopsis. His Act Two aria, however, (“Quando le sere al placido,” among the most beautiful Verdi ever composed) leaves us no doubt that he is a genuine person, and in love. Verdi’s accomplishment lies not only in conjuring up such ravishing melody, but in its dramatic aptness breathing humanity into the written character. Verdi can also dispense with melody when necessary: the Act Two scene between two basses, as Count Walter (Rodolfo’s scheming father) and his henchman Wurm devise evil plots, is marvelously creepy. Another composer might have composed some sort of oath duet but here we have the voices winding in and out of each other, avoiding any obvious tune. It’s hard to tell which character is singing, a neat device when two people are planting ideas in each other’s brains, and a disturbing suggestion of a father’s inappropriate motivations toward his son’s beloved. A truly innovative use (and non-use) of melody comes in the curious finale to Act One. The orchestra carries the melody for several minutes while the characters sing in short phrases, some melodic, others almost spoken. Again, Donizetti had done much the same, but Verdi infuses each snippet with dramatic aptness. A great deal of information can be communicated efficiently, and characters’ motivations (often so unclear in the synopsis) become inevitable. Act Three is a masterpiece of cohesion and humanity. There is a long scene between Luisa and her father, Miller, that can be as heart-rending as anything in Verdi (or anywhere else). Luisa contemplates suicide; Miller sympathetically talks her out of it; she agrees to live and, in order to escape the oppression of Count Walter and his cohorts, the two will wander the hills together as beggars. It will be difficult, but they will have each other, and the purity of their love as opposed to the corruption of the social world. There is gratitude for what they have, lamentation for what they’ve lost, and a sort of numbness from the life blows that have led them to this moment. It is a nexus of emotions so complex and nuanced it can only be depicted in the most austere musical terms (like the “Ah veglia, o donna, questo fior” duet in Rigoletto between Gilda and Rigoletto, another of Verdi’s celebrated father–daughter scenes). It is a wise person’s depiction of a quiet but life-defining moment, and it is inconceivable that this “Hymn to Hope-Within-Disappointment” was written by a man in his thirties. It is also entirely different from his previous opera La Battaglia di Legnano, and is actually more profoundly political. The plight of Luisa and her father sitting in their simple home and evaluating their lives and their future commands our sympathy as much as any king or queen in classical tragedy. The humble have become as significant as the mighty, and the individual as important as the multitude. In its humanity, Verdi’s art achieves what the revolutions of 1848 did not.

William Berger is a writer and radio producer for the Metropolitan Opera. His books include Wagner Without Fear, Puccini Without Excuses, and Verdi With a Vengeance