日曜日 15 年 9 月 19 日 19:30

水曜日 15 年 9 月 22 日 19:30

土曜日 15 年 9 月 25 日 19:30

月曜日 15 年 9 月 27 日 14:00

ルイザ ・ ミラー–

William ベルガー–

ヴェルディのキャリアはそうそれは彼の天才の適切な感謝に対して正しく動作する顕著な-を理解するほどの偉大なヴェルディの仕事があります。誰もが、最上級の疲れたことができます: の「悲劇的な壮大さ」 オテロ と リゴレット、たとえば、またはの「素晴らしい広大さ」 ドン Carlo、またはの「見事に貫通の心理学」 椿姫.しかし誇張は正当かつ必要です。彼のキャリアを通して、特にからの頃 ルイザ ・ ミラー (1849 年) 以降-ヴェルディ作曲それぞれ独自のトーンを持つ傑作のキヤノンか ティンタ 彼はそれと呼ばれる、それは互いからの彼らの多様性および彼らの個々 の利点によって私たちを驚かせます。本物の人間の感情の明確な影響を受けない、宝石質探査、オペラを超えるないと ルイザ ・ ミラー.

元の素材が良い: 演劇 カバレ県 und Liebe, (陰謀と愛)、ドイツの偉大な著者フリードリヒ ・ シラー (1759年-1805)、一度 (ヴェルディの作曲家の間で人気 ドン Carlo、 ジョヴァンナ ・ ダルコ、 私 masnadieri、、の部分 ラ フォルツァ ・ デル ・ ディスティーノ ドニゼッティは、彼の作品に触発され、 マリア ・ Stuarda、ロッシーニの ギョーム ・伝える, and the chorus of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9, among others). The outline of the play is fairly straightforward: The son of an official at a ducal court in the Tyrolian Alps and the daughter of a middle-class musician fall in love; the boy’s father wants him to marry the duke’s mistress instead; plots are concocted to ruin the love affair, and the girl’s parents are arrested; in order to save them, she writes a false letter expressing love for another man and swears it is true; the boy confronts her and, as she dies, she reveals the truth.The crux of the drama is the confrontation of middle and upper class worlds. Representing the middle class on stage at all was an aspect of a radical new genre, the “bourgeois tragedy.” Before this time, tragedy was the exclusive domain of the nobility. This was more than mere elitism. Nobility and royalty by definition represent multitudes of people: hence Shakespeare’s confusing use of titles for characters, (cf. “Norway” in 『 ハムレット 』).我々 は多くの言語 (、英語ではなく) で同じ現象を参照してください今日: ランデブー/voi/現在forms in the Latin languages, ihr ドイツ語、等。重要な人々 が複数の人物との古典的な悲劇の特大の感情が適切なサイズします。18 世紀のドイツの作家を始めた共通の個人に同じ威厳を配し、結果、魅惑的な中に極端な見えた。これがなぜのスポークを人々 は部分的 シュトゥルム und ドラング (storm and stress) to describe these dramas. The emotions had not grown; the people expressing them had “shrunk,” in a sense. Making this same transition from nobles to commoners was a similarly fraught process, and the operas of the later nineteenth century dealing with everyday people are the ones people think of as shrill. It was fine for royals in early operas to wail and gesticulate extravangantly, but when “common individuals” like Santuzza in Mascagni’s カヴァレリア ・ ルスティカーナ express the same levels of emotion, suddenly opera becomes overwrought for many people. Verdi negotiated the conflicting parameters brilliantly, especially in Luisa Miller.

In 1849, the opera was contracted for the great San Carlo opera house at Naples, whose reactionary air was uncongenial for the radical Verdi. In fact, he swore he would never produce another opera there (and he never did, despite a tortured attempt with Un Ballo in Maschera in 1859). But he did get to work again with the great Neapolitan librettist Salvadore Cammarano, with whom he had just collaborated on the sensationally patriotic opera La Battaglia di Legnano in Rome. More famously, Cammarano had written the excellent libretto for Donizetti’s Lucia di Lamermoor in 1835. (Verdi would collaborate with him once again on the intense イル ・ トロヴァトーレ」 4 年間と Cammarano その台本を完了する前に死亡した)。Cammarano は見事シラーの戯曲を合理化します。いくつかの最後の分の変更、およびない以降の編集があった。経験豊かなプロ Cammarano 書いたものは今日何を得る。

ドラマからオペラへの旅が無痛でした当然のことながら、-それは。しかし、物語の焦点をシフトする必要な合理化を提供しています。シラーの宮廷生活のささいなドイツの専制君主の専制政治批判など、 カバレ タイトルの (陰謀)-、奪われている、Liebe (愛) を強調しました。これは、(ただし、彼はそれを達成した)、ナポリの王党派の検閲官を喜ばせるヴェルディのケースではありません。実際にはヴェルディが彼が書いたときに政治するより深い方法を発見しました。 ルイザ ・ ミラー も彼は以前イタリアの愛国心のチーフ音楽マウスピースとして表明していた。

差出人 ナブッコ (1843 年)、ヴェルディは、インスピレーションを提供する、不当の横暴に対して、(多くの場合) で国民の蜂起のテーマを描かれていた実際の新興のイタリア統一運動のコーラスを結集、 リソルジメント.ポイントは、劇場の外に出るし、すぐに (大抵オーストリア) の敵に対して武器を取るに聴衆のメンバーを刺激することでした。後期 1849年によって状況が変わっていた。1848 年に勃発した革命の波は発売されていません。今年が終わった時点で、反動勢力のあった明確に再確立自体より顔をゆがめて。必要な変更は、パリ、ミラノ、ドレスデン、またはどこか他のバリケードに起こらないでしょう。革命は、想像していたもの以外のものにするでしょう。リヒャルト ・ ワーグナーは、ドイツから亡命中の彼の介入の後反乱のフロント ラインは彼の革命的な希望を再調整しの国民の神話の更新を検索します。ヴェルディは、個人でそれを見つけるでしょう。

It is a mistake to think that “the political Verdi” refers only to the patriotic choruses of his early operas. Verdi’s true and radical political idea was expressed in the notion that the needs of the individual, no matter how humble, are as important as the needs of the great and mighty. Put another way, if we remember the concept of nobles as metaphors for groups of people: the needs of the one can outweigh the needs of the many. So it is in Verdi’s 相田 (1870 年)、奴隷の女の子-王、司祭、将軍といっぱいステージ上社会的最低人-ソロのボーカル ラインと独り言の勝利のシーンで全体の大規模な声楽アンサンブルのフォーカスします。そしてそれは、娼婦ヴィオレッタの 椿姫 彼女だけが彼女の社会環境の道徳的なコンパスであることを示します。社会とその教義 (に対する個々 のリベットの肖像画を描くヴェルディの他の例があります。Stiffelio, Boccanegra, ら)。で ルイザ ・ ミラー、個人のこの好みは利用できる材料の選択と両方ストーリー自体にシラーから存在します。

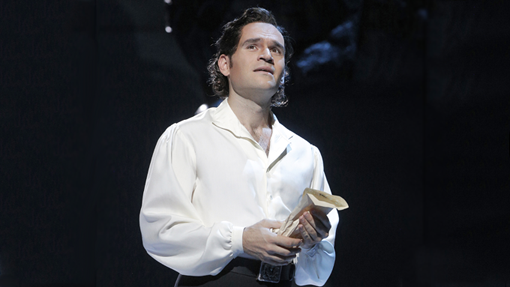

It is a mistake to think that “the political Verdi” refers only to the patriotic choruses of his early operas. Verdi’s true and radical political idea was expressed in the notion that the needs of the individual, no matter how humble, are as important as the needs of the great and mighty. Put another way, if we remember the concept of nobles as metaphors for groups of people: the needs of the one can outweigh the needs of the many. So it is in Verdi’s 相田 (1870 年)、奴隷の女の子-王、司祭、将軍といっぱいステージ上社会的最低人-ソロのボーカル ラインと独り言の勝利のシーンで全体の大規模な声楽アンサンブルのフォーカスします。そしてそれは、娼婦ヴィオレッタの 椿姫 彼女だけが彼女の社会環境の道徳的なコンパスであることを示します。社会とその教義 (に対する個々 のリベットの肖像画を描くヴェルディの他の例があります。Stiffelio, Boccanegra, ら)。で ルイザ ・ ミラー、個人のこの好みは利用できる材料の選択と両方ストーリー自体にシラーから存在します。As always in Verdi, we learn about a character’s true humanity through his or her singing. Melody would become suspect by the end of the nineteenth century and almost regarded as an enemy in the twentieth. In many operas of the early nineteenth century, however, it expresses levels of sincerity. In Donizetti’s Lucia di Lamermoor、テナー エドガルドは、あらすじでは同情ではありません。最悪 (オペラのテノールに一般的な文字の欠陥) を信じるように彼の機敏さはルシアの彼の愛の誠意に質問私たちになります。まだ誰も彼のメロディーを聞く人、特に、彼の最終的な墓のシーン-彼の愛を疑うことができます。メロディーは、彼を検証します。これはトートロジーに聞こえるが、それは (おそらく Cammarano の影響)、ドニゼッティの前に同じ道をしたこと。モーツァルトは、この劇的な方法でメロディを使いません: とのメロディーの美しさに誠実な人は言うことができません。 コジ ・ ファン ・ トゥッテ、最も明白な例を引用するだけ。しかし、ヴェルディがよくドニゼッティのレッスンを学んだ。で ルイザ ・ ミラー, the tenor role, Rodolfo, doesn’t transcend the hoariest clichés about the species when we read the synopsis. His Act Two aria, however, (“Quando le sere al placido,” among the most beautiful Verdi ever composed) leaves us no doubt that he is a genuine person, and in love. Verdi’s accomplishment lies not only in conjuring up such ravishing melody, but in its dramatic aptness breathing humanity into the written character.Verdi can also dispense with melody when necessary: the Act Two scene between two basses, as Count Walter (Rodolfo’s scheming father) and his henchman Wurm devise evil plots, is marvelously creepy. Another composer might have composed some sort of oath duet but here we have the voices winding in and out of each other, avoiding any obvious tune. It’s hard to tell which character is singing, a neat device when two people are planting ideas in each other’s brains, and a disturbing suggestion of a father’s inappropriate motivations toward his son’s beloved. A truly innovative use (and non-use) of melody comes in the curious finale to Act One. The orchestra carries the melody for several minutes while the characters sing in short phrases, some melodic, others almost spoken. Again, Donizetti had done much the same, but Verdi infuses each snippet with dramatic aptness. A great deal of information can be communicated efficiently, and characters’ motivations (often so unclear in the synopsis) become inevitable.Act Three is a masterpiece of cohesion and humanity. There is a long scene between Luisa and her father, Miller, that can be as heart-rending as anything in Verdi (or anywhere else). Luisa contemplates suicide; Miller sympathetically talks her out of it; she agrees to live and, in order to escape the oppression of Count Walter and his cohorts, the two will wander the hills together as beggars. It will be difficult, but they will have each other, and the purity of their love as opposed to the corruption of the social world. There is gratitude for what they have, lamentation for what they’ve lost, and a sort of numbness from the life blows that have led them to this moment. It is a nexus of emotions so complex and nuanced it can only be depicted in the most austere musical terms (like the “Ah veglia, o donna, questo fior” duet in リゴレット ギルダとリゴレット、ヴェルディの別のものを祝う父-娘のシーン)。それは賢明な人の描写が静かな生活を定義する瞬間のそれは彼の 30 代の男でこの「賛美歌を希望-内-失望」が書き込まれたことは考えられない。また、彼のオペラは以前から全く別です。 La Battaglia di Legnano、、実際にはもっと深く政治的。ルイーザと彼女の父親は、簡単な自宅で座っていると自分たちの生活と、将来の評価の窮状のコマンドお見舞いとして多くの王や古典的な悲劇の女王。謙虚は、強大なと個々 の多数と同様に重要として重要なものとしてなっています。その人間性にヴェルディの芸術は、1848 年の革命はしなかったを実現します。

William Berger is a writer and radio producer for the Metropolitan Opera. His books include Wagner Without Fear, Puccini Without Excuses, と Verdi With a Vengeance